A love of Africa’s arts and crafts

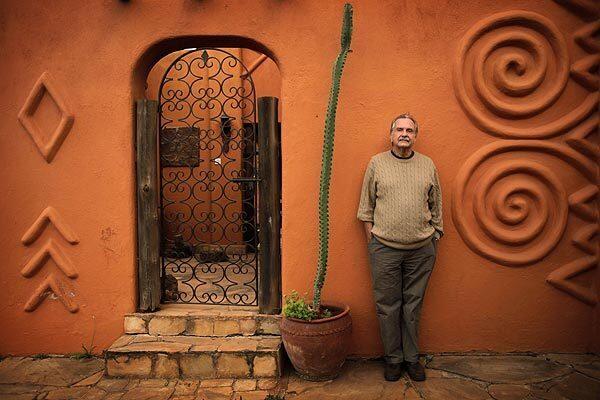

Alan Donovan, 70, was born in Colorado and attended UCLA but has lived in Africa since the U.S. State Department sent him to Nigeria as a relief officer in 1967. His home, billed as the most photographed on the continent, owes its architectural flourishes to sources ranging from Nigerian mud palaces to Timbuktu mosques. Inside are 6,000 pieces of arts and crafts reflecting a lifetime’s immersion in Africana as a collector, dealer and patron. Every detail is carefully arranged, from the sinks of Moroccan brass to a bathtub of Swahili plasterwork. (Barbara Davidson/Los Angeles Times)

American Alan Donovan fostered the continent’s crafts for decades. His home in Kenya is a trove of Africa’s aesthetic riches and a mausoleum of its extinct wonders

Inside are 6,000 pieces of arts and crafts reflecting a lifetime’s immersion in Africana as a collector, dealer and patron. Every detail is carefully arranged, from the sinks of Moroccan brass to a bathtub of Swahili plasterwork. Tour the halls corridors with the owner, however, and the recurring theme is loss. Here is a wall of exquisite beadwork from the Kambas of Kenya. “They’ve become modern, globalized,” Donovan says of the Kambas. “So they’re no longer interested in beadwork.” Here are appliqued masquerade costumes from the Ibos of Nigeria. “You couldn’t get these anymore,” he says. (Barbara Davidson / Los Angeles Times)

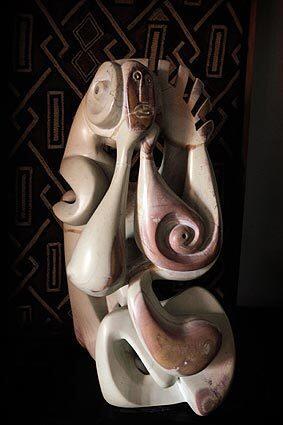

Stone sculpture by John Odochameny, one of East Africa’s pioneer artists. This Sculpture, created in the 1980s, is among the private collection of Alan Donovan at the African Heritage House. (Barbara Davidson / Los Angeles Times)

“Mass Communications I” by John Odochameny, created from the debris of the technological age: typewriter, printing press, microphone, truck piston, etc. Odochameny taught sculpture at African Heritage in the 1980s. His recent works include the series “Mass Communications II,” which include more modern items like cellphones. Odochameny recently suffered a stroke and is partly paralyzed. (Barbara Davidson / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

“Mass Communications II” by John Odochameny, created from the debris of the technological age. (Barbara Davidson / Los Angeles Times)

To find the house that Alan Donovan built, drive southeast from the heart of Kenya’s traffic-snarled capital and pull onto an abruptly quiet road toward the savanna. The African Heritage House, which overlooks the great, still plain of Nairobi National Park, is both a trove of a continent’s aesthetic richness and a mausoleum of its extinct wonders. (Barbara Davidson / Los Angeles Times)

One of Alan Donovan’s loyal staff members. (Barbara Davidson / Los Angeles Times)

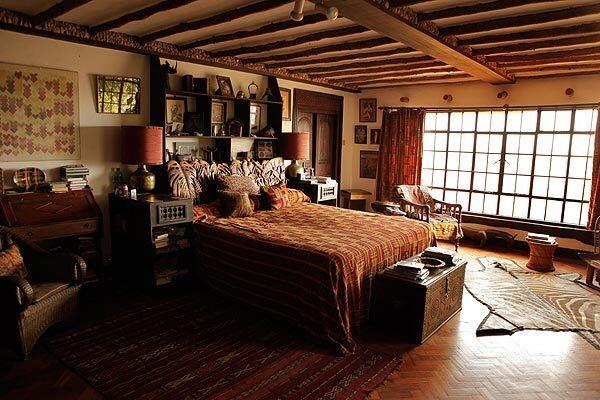

Inside are 6,000 pieces of arts and crafts reflecting a lifetime’s immersion in Africana as a collector, dealer and patron. Every detail is carefully arranged, from the sinks of Moroccan brass to a bathtub of Swahili plasterwork. (Barbara Davidson / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Apart from the Heritage House, Donovan has helped upgrade the art collection in Kenya’s national archives and preserved the collection of the late Murumbi. He also launched a program to save the lion population in the national park. The goal is to persuade Masai pastoralists -- with cash compensation -- not to kill the lions when their cows and goats are mauled. Donovan would like to add six more suits to his house but isn’t sure he has the stamina to complete it. Nor is he sure what will happen to the house when he’s gone. He has no children. “I was going to will it to a foundation before I die, so I can live here,” he says. (Barbara Davidson / Los Angeles Times)

The African Heritage House. (Barbara Davidson / Los Angeles Times)

Alan Donovan’s master bedroom, where he sleeps. (Barbara Davidson / Los Angeles Times)

Exquisite beadwork from the Kambas of Kenya. (Barbara Davidson / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

More beadwork from the Kambas of Kenya. (Barbara Davidson / Los Angeles Times)

More artwork from Alan Donovan’s collection. (Barbara Davidson / Los Angeles Times)

The view from Heritage House. (Barbara Davidson / Los Angeles Times)