Last chance: 6 must-see works before LACMA Islamic Art galleries close

- Share via

T he L.A. County Museum of Art is known for a lot of things: its giant rock, its rack of lampposts and that crazy mint-green building by Bruce Goff that looks like a totally '70s samurai helmet. But it also has an extraordinary collection of art from the Islamic world, with more than 1,700 objects dating back to the early Islamic era (which began in the 7th century). The collection includes an ethereally translucent 14th century Egyptian lamp, a majestic 16th century Iranian silk rug and an entire fountain harvested from an 18th century Syrian home.

These objects are generally housed on the fourth floor of the museum's Ahmanson Building — but not for much longer. The collection is scheduled to hit the road. In 2015, the museum's holdings will travel to Chile and Mexico, as LACMA's Islamic art curator, Linda Komaroff, noted in this post on Unframed, the museum's blog. Starting on Monday, the galleries will be shut down to remove all of the objects for travel, and make way for other exhibitions (including a show of contemporary art from the Middle East, scheduled to open in January).

This means you've got this weekend — and this weekend only — to see some of the finest pieces of Islamic art in the world before they go trotting around the globe.

"If people want to see a different side of Islam, this collection will help them do that," Komaroff said. "It's visually delicious. And it contains so many pieces that are unexpected and out of the ordinary."

There is a lot to see — the museum has been collecting art from the Islamic world since the early 1970s. But here's a guide to six pieces not to miss:

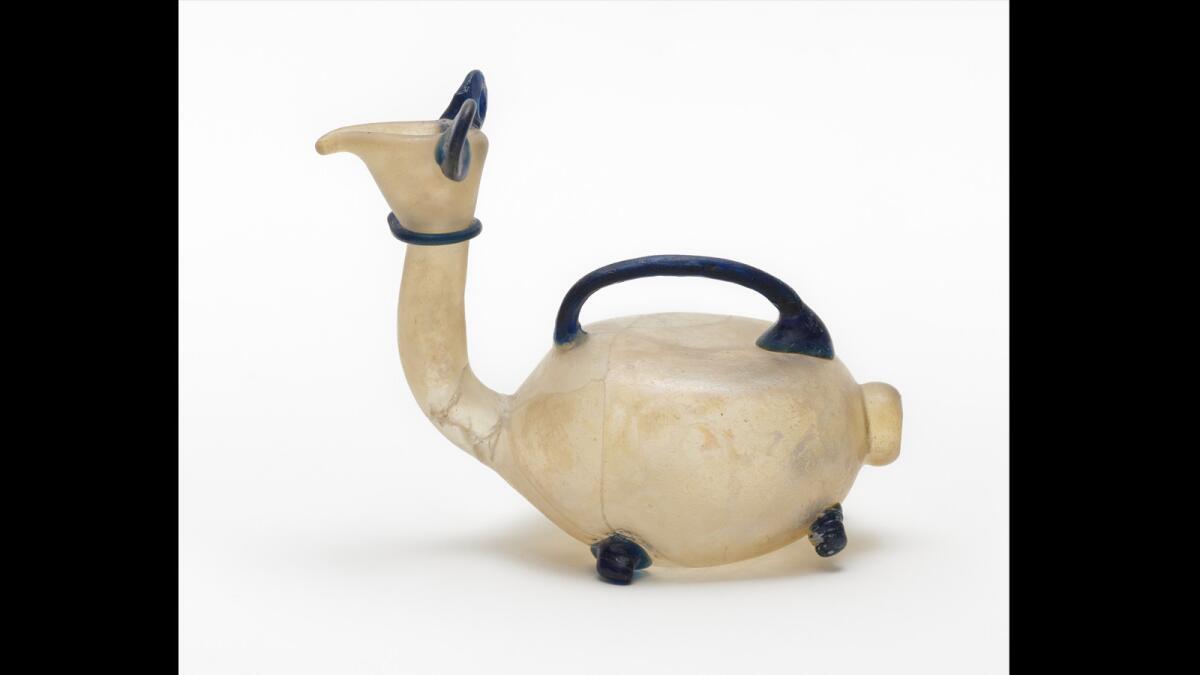

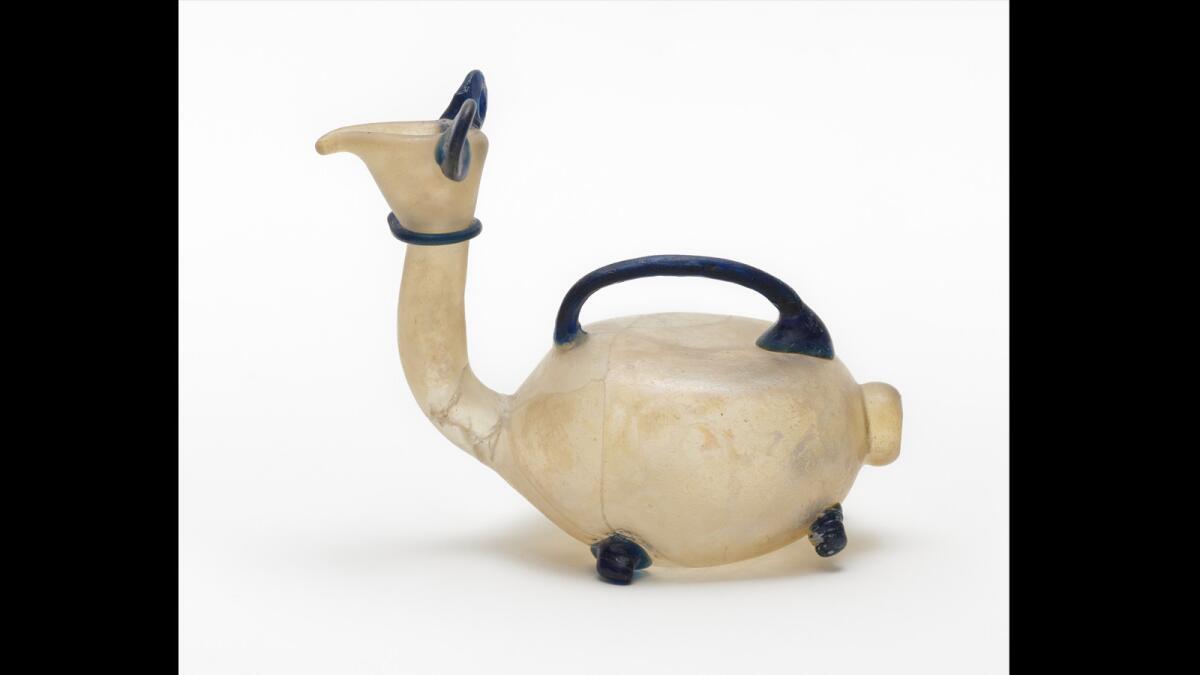

A CHARMING — AND FRAGILE — CAMEL-SHAPED VESSEL

Museum Associates / LACMA

This delicate glass container in the shape of animal (certainly a camel) was made at some point in the 10th century, probably in Iran — and it's pretty wondrous. Made out of blown glass, it is diminutive, fitting easily into the palm of a child's hand. The animal shape makes it charming, but it's also incredible to consider its fragility. As in: How did an object this delicate manage to attain a life span of more than a thousand years?

The vessel was likely used in a domestic setting, said Komaroff: "It's functional. And someone would have handled it on a regular basis because it probably held perfume."

But what sets it apart, she said, is its whimsy. "It's a playful object," she said. "For whatever reason, there's this stereotypical image that art from this region is humorless. But that's anything but the case. And you see that with this container. It has such humor. This is something that we don't generally attach to early cultures or people. Humor is hard to translate through the ages. But this piece achieves that."

10TH CENTURY BOWL WITH CALLIGRAPHY

Museum Associates / LACMA

A number of the pieces in the collection feel incredibly contemporary, even though they might have been crafted a millennium ago. A white ceramic bowl ringed in blocky, stylized calligraphy looks like the sort of thing you might find in a hipster-y home design shop. But it was produced in the 10th century, somewhere in greater Iran, Nishapur or Samarqand. The words come together to form an aphorism, "Frugality is a symptom of poverty."

"'Greed is a symptom of poverty,' is another way of translating it," said Komaroff. "It was typical in the 10th century, in the eastern Iranian world, to have these sayings on fairly expensive bowls. It's like the sayings we have in our own homes, like 'God Bless Our Happy Home.' And it contains an especially beautiful and elegant script."

This also gets at a common motif in the art of the region: "In the Islamic world, everything is talking to you," Komaroff said. "So much of it is inscribed with texts. There is a two-fold purpose for writing: the first is to convey information and the second is to decorate." Interestingly, it too contains a touch of whimsy. "There would have been food served inside the bowl," Komaroff explained. "So as the bowl emptied you could read the inscription more clearly — which has to do with greed."

TILE IN THE FORM OF THE LETTER 'WAW'

Museum Associates / LACMA

When I lived in New York I would regularly pop into the Islamic galleries at the Metropolitan Museum of Art to visit a 12th century chess set from Iran that is remarkable for its minimalist qualities. The ceramic tile of the Arabic letter "waw" in LACMA's collection reminds me of those terrifically sleek playing pieces. Crafted at some point in the 12th century, somewhere in Iran, it's all that remains of what was probably some sort of architectural inscription.

"In the Arabic alphabet, the form of a letter can change depending on whether it's in the middle of a word or at the end of a word," said Komaroff. "So this is something that the craftsman would have had to think about as they were fabricating this ceramic piece — which is a three-dimensional representation of language usually only shown in two dimensions. It would have been shaped and fired and glazed. It would have been very time-consuming to make. Even though it's about language, it's beautiful as an object. That's part of the appeal of Islamic art for me. There are multiple ways of experiencing it. Even if you don't read Arabic."

FOUNTAIN FROM A DAMASCUS HOUSE

Museum Associates / LACMA

One of the more spectacular pieces in LACMA's collection is this fountain, made from marble and painted limestone, which would have been part of a home in Damascus, Syria, in the 18th century.

"It comes from a reception room that dated to 1766," Komaroff explained. "Like a lot of Islamic art, it is beautiful and functional. There would have been some kind of faucet on it. People coming into the room might have been offered water from it, and it wouldn't be uncommon that they'd make coffee next to it."

And it would have served as an important symbol of status and hospitality. "It sat opposite the entrance of the room so it would have been a focal point," she adds. "The upper part of the walls of the rooms, the cornices, were decorated with fruit: watermelon, pears, maybe cherries. So as you look up there, you're anticipating the refreshments that might be offered. Reception rooms are about pleasure and about being entertained and well-fed. The fountain was part of this larger architectural ensemble, matching the floor of the room and there would have been a decorated arch, too. It would have come from a well-to-do home, the equivalent of someone living in Beverly Hills or Brentwood."

WOOD PANEL FROM IRAN

Museum Associates / LACMA

"This is a pretty rare piece," said Komaroff, of an elaborately carved wood panel from Iran that likely served as some sort of architectural ornamentation and that dates to the 14th or 15th century. "At the time this was made, wood was a luxurious material and not much of it has survived from that period." In fact, in this panel's painted surface, only the red survives. "It would have been very bright," Komaroff said. "It likely came from something really important, like a religious building, or a pulpit, or a secular administrative building. But it would have been someplace special because it would have been very expensive."

FLORAL JUGS THAT MAY HAVE INSPIRED MATISSE

Museum Associates / LACMA

These floral-patterned jugs, which were made in the late 15th or early 16th century, likely in Iran or somewhere in Central Asia, are not only beautiful, they have a terrific story. "They were in an exhibition in Munich in 1910," Komaroff said. "The first big European exhibition of Islamic art, with hundreds of objects. We know that [Henri] Matisse went to the exhibition. I don't know that Matisse saw these particular pieces. He may have missed them. But he likely saw something similar. And after seeing the show, we know that not long after he goes to Morocco. So, it serves to remind us that artistic ideas travel, artists travel. The lighter one reminds me of some of the forms we see in Matisse's cut-outs later on."

Like a lot of art from the region, it is also highly portable and functional — and it gets at an aspect of culture that some might find quite surprising. "These would have been for some kind of liquid, possibly wine," said Komaroff. "In the Iranian world, wine drinking never quite disappeared. If you read Persian poetry, it's filled with metaphors about wine. So it's kind of sad that many people don't know that Shiraz is named after a city in Iran, not Australia."

LACMA's Islamic art galleries will be open to the public through Sunday, 5905 Wilshire Blvd., Mid-Wilshire, Los Angeles. lacma.org.

Find me on Twitter @cmonstah

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.